This pot is a design gem, one of the most elegant pots of the hundreds in the collection. But it is also a masquerade.

The two “hummingbirds” are a variation of the Sikyatki “man eagle” design. (See the Category List.) The design beautifully fits the shape of the pot and reflects several of the design characteristics that make “Old Lady” Nampeyo’s pottery great:

1) The curvilinear sweep of the birds contradicts the linear elements of the central “flower.” The liner design on the top rear of the pot pulls the eye away from the curvilinear central image and is itself counterbalanced by the negative and positive arrow images created by the framing ring around the mouth of the jar.

2) Color integrates the design. Three areas of the bird’s bodies are red and the red bird “beaks” and tongues become part of the central “flower.”

3) The central bird images seem to flutter in the empty space around them; much of the reverse side of the pot is empty space, except for the linear element on the top shoulder. Although the pot is small, the design seems spacious.

The gentle blushing of the clay adds energy to the design. Overall, the pot is a treat for the eyes.

Yet things are not what they seem. Pot 2010-10 is an irony: the completion of a 230-year circle of design between Hopi (Hopi/Tewa) and Zuni potters. Aside from the borrowed design and color scheme, there is nothing Hopi about this pot.

The irony that is jar 2010-10 is understood by a review of Hopi ceramic history:

From about 1360 to 1500 CE coal-fired “Jeddito” yellowware, often with curvilinear avian designs, was the iconic Hopi ceramic. (See LeBlanc and Henderson, 2009; Hays, 1991 and “Jeddito” in the category list.)

During the late 18th century and much of the 19th, smallpox (introduced by the Spanish) and draught frequently inflicted the Hopi mesas (Rushforth and Upham, 1992). When these disasters struck Black Mesa, many fled Hopi and found shelter with relatives at friends at Zuni. When they returned to Hopi they brought the knowledge of Zuni pottery techniques with them. These Hopi “Polacca ware” pots are not distinguishable from their Zuni contemporaries unless there is a chip that permits analysis of the core clay. Both are thick-walled, slipped with a white slip that crackles upon firing, use red and black paint and employ the same designs; Arabesque and “rain bird” motifs are common. (See the Category List for examples.)

As early as the 1880’s, but certainly by the 1900, the production of crude white-slipped ware at Hopi was replaced by pottery that reflected the older Jeddito (and specifically Sikyatki) style of pottery. (See the discussion in Appendix A.) Nampeyo is the best-known maker of such “Sikyatki Revival” pots; most were made for sale to Anglos. This “Revival” pottery is now synonymous with “Hopi” (and “Tewa-Hopi”) pottery.

Moreover, Hopi grey clay has the unusual property of blushing a tan/gold when fired, with variations in tone due to variations in wind and thus the hotness of the dung fire. As has been traditional for all southwestern pueblo pottery for several hundred years, Jeddito, Polacca and Sikyatki Revival pots are constructed by building up coils of clay on a concave base and then smoothing, shaping and sanding the clay before painting. (The exceptions are coil baskets begun in a basket form. The coil construction sequence and color variation in the clay are particularly evident in bowl 1995-11.)

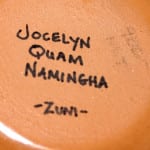

Pot 2010-10 looks like a typical Sikyatki Revival Hopi pot. Though more skillfully done than most, it displays a version of the classic man-eagle design, seems tan/gold blushed and (as noted above) incorporates several of the design techniques that characterize Nampeyo’s work. Yet on most counts it is a sharp departure from Hopi pottery traditions. The clay used is not from Hopi and is probably commercial. The pot was formed on a wheel and fired in a kiln. The tan “blushing” does not seem indigenous to the clay used but seems added, perhaps by using a tan/gold slip. The potter, Jocelyn Quam Namingha, in not Hopi. She was raised by Zuni parents at Zuni. Her husband (Les Namingha) has a Zuni mother and a Hopi/Tewa father and was also raised at Zuni. (Les’ aunt is Dextra Quotskuyva, great granddaughter of Nampeyo. Dextra taught Les to make pottery; he taught Jocelyn.)

If Polacca ware pottery is Hopi pottery that looks Zuni but is not, pot 2010-10 is an innovative Zuni pot that looks Hopi, but is not. Jocelyn accurately signed the pot “Zuni.” With pot 2010-10 the circle of influence from Polacca ware to Sikyatki Revival ware has come full circle.

Most of my life is spent traveling in great circles, so this makes a kind of sense to me.

For a Hopi vase with a folk art version of this same hummingbird/flower design, see 2010-18. The discussion of that pot suggests a Hopi understanding of this design.