This bowl began as an enigma clearly proclaiming a false origin, its maker uncertain. Ten years after I purchased this pot, I purchased another. The more recent purchase clarified the origin of pot 2010-20. It’s been a fun journey of discovery.

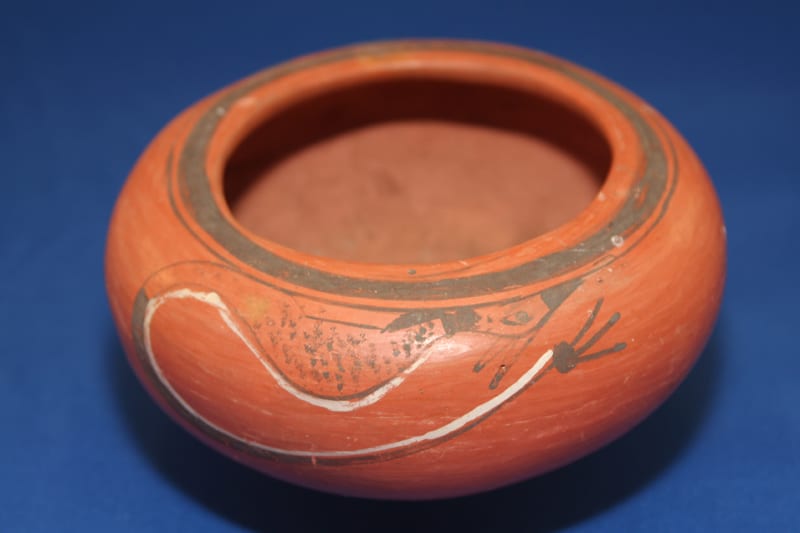

The bowl is unslipped and made of “sikyatska,” yellow clay that fires red. The base is particularly thick, and the walls are somewhat thinner, which makes the pot quite heavy for its size. The form is not particularly graceful. Except for one white line, the design is monochromatic. The orientation of the decoration is odd. When the bowl is sitting on its base, the decoration is upside down and appears to be a series of sagging lines and doodles. The photographs of the pot sitting on a table in the eBay listing were out-of-focus, which made the design even more incoherent. Only after the pot was received and could be seen from directly above did the designs resolve themselves into two inverted abstracted animals (perhaps mice).

The design is casually painted. For example, the thick-above-thin framing lines around the pot opening are inexactly drawn so that the space between the opening and the first line and the space between the two lines vary in width. The two animal figures are different from each other, but both are casually drawn. The figure with the white (kaolin) clay line outlining its back and tail has a black element behind the head that intrudes into its speckled body and a solid black tail ending in a ball and line element. Fewekes interpretes this design as representing prayer feathers (pathos) suspended from a string (nakwakwoci), the typical parayer offerings at Hopi (1973:138-140).

The second animal figure has a black element behind the head that is forward pointing and does not intrude into the speckled body. The tail on this latter animal is not solid black for the first two-thirds of its length but incorporates a box and line element that is unevenly drawn and the tail lacks the ball and line ending. If it were not for the paper label on the bottom, this bowl would be simply a poorly formed Hopi pot with an interesting but awkwardly conceived and placed design.

Charles King had a pot for sale in 2021 with a finer version of this animal design. Of it he wrote:

“The design on each side is interesting. It looks a bit like a bird (the head) and at times I thought it looked like a fox. However, I did ask Dextra Quotskuyva about this same design on one of her pieces and she said it was a lizard. Strangely enough, I can kind of see it with the long tail and maybe the ‘ears’ are the crest on a lizard. Needless to say, I go with it as a ‘lizard.’ “

What is extraordinary about the pot is the paper label on the bottom: “Made by Nampeyo—Hopi.”

The Fred Harvey Company heavily promoted Nampeyo: she opened the company’s “Hopi House” at the Grand Canyon in 1905 and she and her family returned to be “artists in residence” in 1907 (Kramer, 1996:171).

A turn of the century Santa Fe railroad booklet notes, “Nampeo, at Hano, is the best potter in all Moki-land (Hough, 1899:48) (“Moki” is an older and disreputable Navajo term for the Hopi.) A 1903 Atchison-Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad book notes that the Tewa of Hano “are the most skilful potters of all this region, while the ware of old Nampeyo and her daughter have gone far and wide over the curio-loving world (Dorsey, 1903:108).” The daughter was Annie, who would have been 19 the year the book was published. A 1913 travel guide to the southwest mentions “Nampaii, the wonderful woman pottery maker from First Mesa (Laut, 1913:132).” Harvey publications featured her and evaluated Nampeyo pots as “the most artistic among Indian products” (Fred Harvey Co, 1914?, unnumbered). Writing in 1915, Walter Hough noted that “Everyone who visits Tusayan (Hopi) will bring away as a souvenir some of the work of Nampeyo the potter (1915:75).”

All this promotion made Nampeyo the first Native American artist to be recognized by name in the Anglo world. Herman Schweizer of the Fred Harvey company regularly commissioned groups of pots from Nampeyo and had special labels made to distinguish her pots from others. Most Hopi pots sold by the Harvey Co. had the label “From the Hopi Villages” affixed to the bottom (cf. 1997-02 and 1999-13 in this collection). Pots by the master from about 1902 to about 1920 were marked with the Nampeyo label seen on bowl 2010-20 and thus commanded higher prices (Kramer, 1996:86).

Unable to write, (Nampeyo’s) pottery went unattributed until the Harvey Company supplied labels, glued to the undersides of her pots, that identified her as maker. These labels are now recognized as a possible guarantee of authenticity, and they add to the value of the pot (Blairs, 1999:88).

To enhance the value of the vessels made at Hopi House, small black and gold stickers proclaiming “Made by Nampeyo, Hopi” were affixed to all of the pieces that she made for sale (Kramer 1988:49).

Over the years, many Nampeyo labels wore off (since they were often on the bottom of the pots), fell off, or were removed. The Harvey label on pot 2010-20 is placed off-center on the bottom, thus protecting it from wear. I had seen photographs of the Harvey Nampeyo label but had never held one in my hands until I bought pot 2010-20.

The Harvey label “by Nampeyo” generally is the best contemporaneous guarantee that a pot is an authentic Nampeyo. Yet the form, painting and arrangement of the design of bowl 2010-20are far below Nampeyo’s standard. So, who made and painted pot this pot?

Here are four possibilities:

a) Nampeyo formed and painted the pot, but did so quickly (and thus casually) to fill a Harvey order that would be sold to buyers who simply wanted a “real” Nampeyo pot, regardless of the fineness of design. By 1908 Herman Schweizer was buying “two or three dozen” Nampeyo pots at a time, but had become critical of the quality (Kramer, 1996:103-104).

b) Nampeyo painted this pot when she was becoming blind and could no longer paint accurately (perhaps 1915 to 1920).

I do not find either of these first two possibilities very convincing. The quality of Nampeyo’s work varies (see Appendix D), but I have never seen a Nampeyo pot as thick, heavy, and poorly formed as 2010-20. Even during her last years and blind, Nampeyo made well-formed pottery (cf. 2007-12).

In addition, nothing about the painting suggests it was done by Nampeyo. A very high percentage of Nampeyo Sikyatki Revival pots are framed with thick-above-thin framing lines. Her framing lines are always even and precise with uniform space around them. From practice I suspect Nampeyo could draw these framing lines perfectly in her sleep. The uneven, inaccurate framing lines on bowl 2010-20 do not look like her work. Similarly, the two animal images are drawn with a shaky, hesitant hand that looks nothing like the practiced painting of Nampeyo.

I have seen quite a few Nampeyo bowls and have viewed photographs of many more. In all cases that I am aware of, the designs on the exterior of Nampeyo bowls were meant to be seen right side up when the bowl was sitting on a table. The contrary is the case with bowl 2010-20. I am guessing that, even when she was rushed to fill a Harvey order, Nampeyo would have followed her practiced instinct and placed her designs with the normal orientation on the bowl exterior.

Thus 1) based on form, 2) the casual, uncontrolled painting, and 3) the unusual orientation of the design, I don’t believe that Nampeyo either formed or painted bowl 2010-20. The pot is mislabeled as “By Nampeyo — Hopi.”

Two possibilities of maker remain:

c) The pot was formed and painted by a daughter who was young and not particularly skilled. “It is common for Hopi girls to learn the art of molding clay into pottery when they are 12 to 15 years of age” (Ashton, 1976:30). As part of a lot, a Harvey employee would have just assumed the pot was by Nampeyo and put on the label.

–Red clay pots with designs outlined in white kaolin were for a period of time hallmarks of Annie’s work (cf 2018-02). Perhaps she made and painted pot 2010-20. However, Annie was born in 1884 and was 21 when the “Made by Nampeyo” labels were first printed in 1905. By then she was an experienced potter capable of producing pots whose form and painting far exceed pot 2010-20.

–Nellie was born in 1894 and was 10 or 11 in 1905 when she moved with her family to Hopi House at the Grand Canyon for three months, the same year the Harvey “Made by Nampeyo” labels were first printed. A very kind person, she was never a particularly gifted potter or painter. Perhaps this is an example of her early work. At the Grand Canyon, she was far from her playmates at Hano and perhaps bored. It’s speculative but not hard to imagine that while her mother was employed making pottery at Hopi House, young daughter Nellie also tried her hand at pot making. That was the normal way daughters of her age learn how to pot. Bowl 2010-20 may be an early attempt by a young Nellie to form and paint pottery, borrowing her Mother’s design and applying it with a child’s hand. It is not hard to imagine a Harvey employee slapping a “Made by Nampeyo” label on anything the family produced, even if made by a child.

About nine years after I had written this catalog entry, I had a chance to buy a jar (2019-08) signed “Nampeyo Nellie” in that order. I interpret this pattern of names as indicating that Nampeyo formed the pot after about 1920 (when she was going blind) and it was painted by Nellie. The pot is painted with two identical avian images. Pot 2019-08 is relevant here for three reasons: First, both pot 2010-20 and pot 2019-08 have the same basic layout: thick over thin framing lines and below them two renditions of an animal, although the quality of the painting on jar 2019-08 is much better. Second, the heads of the animals on the two pots are very similar and of an unusual design: shaped like a half-moon with a long beak, oval eyes and two triangular crests, chins resting on the ground. Third, and most startling, on both of these pots the animal designs are inverted with the bellies near the rim. This is a rare orientation: other than one jar in a private collection, these are the only two Hopi pots with inverted animal images that I know of. We know that jar 2019-08 was painted by Nellie. These three similarities are external evidence that jar 2010-20 was also painted by Nellie. The inverted orientation of the animals was apparently not the whim of a young Nellie, but was a design technique she intentionally used on at least one other pot. Why she did so is unknown.

A Harvey employee would have simply attached a “Nampeyo” label, not knowing or caring that a daughter and not Nampeyo herself made the pot.

–Youngest daughter Fannie (born in 1900 or 1905) was too young to have made this pot when Harvey introduced the “Nampeyo” label in 1905. On the other hand, she was around 15 years old when Harvey stopped using the Nampeyo labels (about 1920), so Fannie remains a possibility as maker of 2010-20. However, the collection does contain a pot (2009-14) that is probably an example of Fannie’s early painting and that painting is much finer than on pot 2010-20.

There is a final possibility:

d) Perhaps bowl 2010-20 was not made by Nampeyo or a member of her family. Perhaps a Fred Harvey employee simply added the “Made by Nampeyo—Hopi” label to an ordinary pot by an unknown maker. This logic fits the data, except that the animal/mouse creatures were one of the motifs used by Nampeyo and her family.

For one example see Collins (1974:28, #30) for a beautifully executed Nampeyo pot with a similar “mouse” design. In 1911 Dr. Barrett from the Milwaukee Public Museum visited Hopi with the express purpose of documenting the stages of forming, painting and firing pottery by Nampeyo. In a article summarizing this collection, Stephen Schwartz publishes a photograph of five pots collected by Barrett, one of them carrying a creature similar to the one on pot 2010-20 (1969:116).

Two other examples are found on tiles that Nampeyo made in 1905, the same year the Harvey “Nampeyo” label began to be used. In that year Nampeyo received a commission from Jacob and Maria Breid. Between May 1904 and July 1906 the Breids were employed as doctors on the Hopi reservation. During this time they apparently arranged for Nampeyo to make a set of 70 ceramic tiles, intending to install them around the fireplace mantle of their home. Probably about half of these tiles were made by Nampeyo herself and the rest probably by Annie (the Messiers, 2007:34-35). These tiles were subsequently given to The California Academy of Sciences and can be viewed online at: http://research.calacademy.org/research/anthropology/collections/Index.asp

using the search word “Nampeyo” as “maker.” Two of the tiles (#CAS 1987-0003-0066 and

CAS 1987-0003-0067) display carefully drawn depictions of the “mouse” design on 2010-20. That records do not indicate whether Nampeyo of Annie made which tile. This does not help identify the exact maker of bowl 2010-20, but it is evidence that the Nampeyo family was using this mouse image about the time the Harvey labels came into use.

I am inclined to give some weight to the Harvey label and “mouse-like” design and believe that bowl 2010-20 is a Nampeyo family product. For a modern Hopi/Tewa pot using the mouse-like creature, see 2010-29 in this collection by Neva Nampeyo.

Given this myriad of possibilities, it’s not the first time I have wished a pot could talk.

Given 1) the circumstantial evidence detailed above and 2) the striking similarity between this pot and 2019-08 that we know was painted by Nellie, I reaffirm my original conclusion that a young Nellie was the maker and painter of pot 2010-20.

Having only seen photographs of the pot, Ed Wade commented that “Strange vessel. The animal is definitely Nampeyo design but the execution is very crude. I’m tempted to say it is a very early Annie but it’s far too crude for her work. I think it is an example of a potter, likely Nampeyo family, practicing the family tradition and the Harvey company put the sticker on not caring who made or painted the vessel.” (Email 11/10/10, on file)

I conclude that this is the work of a young Nellie . The label clearly speaks to the commercial relationship between the Nampeyo family and the Harvey Company. In this case the label also indicates that employees of the Harvey Company were not very discriminating when applying the “Made by Nampeyo, Hopi” label to family pots.