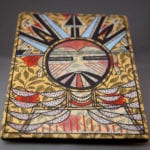

The techniques and materials used to produce this item are innovative, not traditional. The iconography is both innovative and thoroughly traditional. The result is both visually and spiritually stunning. However, this art is only incidentally a pottery tile.

Upon careful examination, this is an acrylic painting on commercially printed cloth that has been glued to a plain pottery tile. For an actual painted tile by Les, see 2022-07.

Native Hopi clay generally has color variations or “blushing” when fired outdoors in a low-temerature dung fire. The gallery that sold this piece says it is made of native clay, which may be accurate. Here the clay is a uniform dull light tan in color. When struck with a finger, it emits a high-pitched sound. Both color and pitch are evidence of kiln firing, even if the clay used was native.

The tile is signed “Les Namingha, 2016” on the back. There is a small drip of red paint on this back.

Les glued a piece of printed commercial cloth to the front on the clay tile and this continues just over the edge. The remaining edge is painted black. The design printed on the cloth is of a vine with small green leaves and five-petaled red flowers; the background is a light yellow-green.

On the cloth Les has painted the image of a Polik’Mana, variously translated into English as “Corn Grinding” or “Water Bearing” girl or “Butterfly Maiden.” The Pahlik Mana is not considered a kachina. When appearing in the plaza during the fall social dances, she wears an elaborate headdress of linear and curvilinear elements that are symbolic of rain clouds, corn, and fertility (Branson 1992:173). Her multiple roles can be confusing (Wright, 1973:106). “She” can have both female and male persona. When appearing as a female, she has red dots on her cheeks (cf 2009-17 and 2013-08). When presenting as a male, the cheeks are decorated with red triangles (cf. 2014-10) as on the tile discussed here.

The depiction of the Polik’Mana on pottery is so standardized that pots made 100 or more years apart have strikingly similar iconography. (See the Category list under “Kachinas” for other pots in this collection depicting the Polik’Mana.) On this tile, the dancer is depicted from the chest up to the top of his tableta. This format is almost exactly the same as on the Polacca bowl by Nampeyo in this collection (2009-17), which dates to the early 1890’s. For Polik’Mana bowls with similar layouts that are part of the Keam Collection in the Peabody Museum, Harvard, see Elmore, 2015:136-138. On tile 2016-02, Les has framed this personage with a thin black line, following the example set by Nampeyo on a tile made 120 years earlier (2014-10).

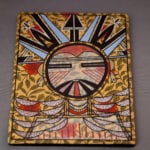

The upper torso of the Mana is indicated by a trapezoid enclosing 14 vertical red lines. From his neck flow 9 pairs of pale half circles, 4 pairs on one side and 5 on the other. These half circles are painted with a pattern of black and red dots and represent a cloak draped over the shoulders of the Mana.

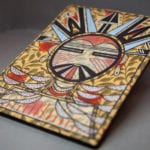

The face of the Mana is drawn within a thick black circle and incorporates the expected elements: a “Darth Vader” triangular mouth, striped triangles on the cheeks indicating a male gender, slit eyes and a forhead consisting of three lines forming a two-lane “highway” surmouinted by two unpainted half circles and a red brow. Teardrop earrings are defined by white and black lines and replace the more usual earrings of square mosaic turquoise.

Surrounding the face is a thin black circle and the tableta headdress is built upon this base. The elements of the tableta are simpler than the usual rendering. The bottom of the tableta is indicated by a horizontal blue band at the level of the forehead. Four thicker and triangular blue rays fan from the top of the Mana’s head, like a Hopi Statue of Liberty. Between the top two blue rays is a black split arrow-head shape. Between the remaining blue elements, on either side of the tableta, are black elements shaped like a “W.” The central point of this “W” is topped by fleur de lis representing squash blossoms.

Les apparently applied a thin white wash to the cloth enclosed by the trapezoid chest and face of the Polik’Man. As a result the vine and flower motif printed on the cloth in these areas is lighter and not a bold as on the rest of the tile.

Given the complexity of the printed cloth and the detailed Polik’Mana image painted on it, there is a great density of design on tile 2016-02. Glanced at, the design seems a jumble of forms. A studied gaze suggests otherwise. Indeed the design is a summary of Hopi beliefs, ethics and vision. For the non-Hopi, an explanation is required.

Siitalpuva

“Siitalpuva” is a place that embodies the essence of the Hopi belief system,

“…a colorful, glittering, flowery paradise.…’along (or throughout) the flowery land,’ ‘along the fields in bloom,’ ‘the land brightened with flowers’ …..This flowery world is not a separate place, like the Christian Heaven, but a reality that can be brought forth in this world… (Hays-Gilpin and Schaafsma, 2010: 122. Also see Hays-Gilpin and Sekaquaptewa, 2006:14).”

“This does not happen automatically — human actions and intentions are necessary, in the form of thoughts, prayer, song, dance, and hard work done the right way. Hopi prayers for moisture and rain enable life in the desert. Without (these), the goal of realizing a shimmering lndscape and flowery, sparking world would never be fulfilled (Hays-Gilpin and Schaafsma, 2010:4).”

Each Hopi village provides a space within which the katsinam visit to sing and dance for the villagers:

“To correct a widely held belief, katsina songs are NOT prayers from the katsinam for a good life for the Hopi. Rather, they are subtle admonitions from the katsinam to the Hopi for the Hopi to recognize and mend their errant ways…If the Hopi follow these life practices, then ‘for their part’ they, the katsinam, will reciprocate with rain that will beautify the landscape with flowering crops…(Hays-Gilpin and Schaafsma, 2010:143-144).”

Tile 2016-02 is a summary of this belief system. The overall green color of the cloth suggests a verdant space. The printed design of vines, leaves and flowers is the personification of siitalpuva. This is the promise underlying the painted Polik’Man who, while not strickly a katshina, dances in the villages to remind the Hopi to live modest, ethical lives that will call forth rain and thus an abundance of blessings.

Is this art appropriate in a Hopi pottery collection?

It’s not clear how this piece fits into a Hopi pottery collection since the clay tile simply serves as a backing for the painting on cloth.

This art is more painting than ceramic, like an oil-on-canvass painting mounted on wood is aesthetically not a wooden object. Yet the dense iconography of 2016-02 has a clear and entirely Hopi message. My Native American collection contains paintings by Dan Namingha, Michael Kabotie and Neal David Sr as well as prints by Fred Kabotie and others, so a painting by Les Namingha still fits within my collection parameters.

To further complicate the story, Les is not “simply” a Hopi artist trained in his village.. He is the son of Emerson Namingha, great-grandson of Nampeyo through Annie Healing. Les’ mother and wife are Zuni and he was raised and lives there. He has a bachelor’s degree in design and is interested in easel painting as well as pottery. He was trained as a potter by his aunt Dextra Quotskuyva the most renowned Hopi/Tewa potter of her generation. Thus he draws from a rich but not entirely Hopi heritage to fuel his art. .

Finally, for all my doubt about tile 2016-02 being appropriate in a Hopi pottery collection, a viewer sees it as a tile with a Polik’Mana image and this places Les’ work as a direct descendant of earlier Hopi pottery tiles, most especially tile 2014-10 by Nampeyo.

Even the gallery that sold 2016-02 saw it as paint-on-tile and did not recognize the construction of the piece. They described it:

“…This tile is made from native clay and painted with acrylic. The design is a classic Butterfly Maiden Kastsina Mask…Here Les has not only added color but his classic pointillism as part of the painting. It’s the background, with the intricately painted leaves, which works so beautifully for this piece…”

What the gallery saw as painted pointillism is commercially printed cloth. When I received the tile and recognized that the painting was on cloth, not clay, I contact the gallery and they contacted Les and he confirmed the construction:

“I did check with Les and it is acrylic and collage on that specific piece. It is actually native clay, cloth on the top and the acrylic painted on top of that…Yes, the flower design is pre-printed cloth/paper. The only painting is the butterfly maiden (emails from Charles King, 2/22 and 2/23/16.”

Charles asked Les about tile 2016-02 and Les responded:

“Years back I used cloth material on some pots for Robert Nichols. Liked the results and planned on doing some more collage works at some point. Recently, my mother being a seamstress had a nice collection of scrap cloth, which led me to decide to use some of those prints, that had interesting patterns, on some tiles and pots. The color and floral print were perfect for the Hopi palik mana. Most of what my mom sews together are for ceremonial purposes; men and women’s shirts and dresses for dances (at Zuni). So there was a connection with the figure and my mom ‘dressing’ her. (Email from Charles King, 2/26/16 on file).”

Thus the use of cloth printed with verdant vine and flowers is not an accident, but was chosen by Les’ Mother to be used in Zuni village kasina dances and then repurposed by Les as a symbol of Siitalpuva that would be appropriate for a Hopi Polik’Mana image. Although the construction of the tile 2016-02 was determined by Les’ proclivity to find new ways to express his art, the intentionality of the materials and design is part of traditional pueblo culture.

I’m not sure if the intricacy and detail of design on tile 2016-02 would even be possible with a paintbrush. I aappreciate that the gallery quickly contacted Les to determine the true nature of the tile and was entirely open to my returning it. Taking all of the contradictory tensions of the above discussion into account, I made the decision to keep “tile” 2016-02 as both a compelling piece of art and an example of how much similarly and difference there is between this Polik’Mana “tile” and the one made by Nampeyo about 120 years earlier (2014-10).

My need to define art into a singular category of “painting” or “pottery” says more about my limitations of imagination than it does about the aesthetic value of tile 2016-02.

For a depiction of the Polik’Mana by Les’ 14-year-old son Josh, see plate 2019-03.