This is a particularly interesting pot because it documents an inovative departure from the standard of Hopi-Tewa pottery. The names “Wallace Youvella” and “Iris Nampey” are inscribed on the bottom, followed by the numbers “4-75.”

Iris is the daughter of Fannie Nampeyo, Nampeyo of Hano’s youngest child. Fannie was a talented and prolific potter for many years and closely adhered to her Mother’s Sikyatki Revival techniques and designs. Fannie had seven children and most of them were also traditional potters. (See “Arist List” for Elva, Leah and Tonita Nampeyo.) Two of Fannie’s younger children, however, deviated from their Mother and siblings. In the early 1970’s Thomas (b.1935) began to innovate his potery. Inspired by potters in Santa Clara Pueblo 200 miles east of Hopi, Thomas began to incise his pots and sometimes added turquoise after firing to embellish the design. (See 2005-09.) Traditional firing often damages pottery. Thomas bought a kiln to lower his loss rate.

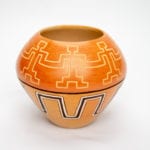

Pot 2017-11 is evidence that younger sister Iris (1944–2018) and her husband Wallace were inspired by Thomas. The pot is thin and even. When struck with a finger it resonates with a high pitch; the pot lacks blushing. Both of these characteristics are evidence of kiln firing. A dremel tool, was used to incise a black line around the jar’s waist. Above this line the surface is a darker redish tan. The dremel tool was used to cut down to the unpolished clay beneath the surface to incise a continuous chain of eight squared-off human figures, sort of a Hopi chorus line.. Below that waist the pot narrows to a base. A zigzag line was engraved on the lower half of the pot. Eight square convex steps of this line reach toward the chorus line above and are centered between the human figures. Each concave line between the steps narrows at its base in order to fit the narrowing shape of pot. The zigzag design is formed from two etched and parallel lines. These depressions are painted white; the raised surface between them is painted black.

Very similar squared-off human figures, presented individually with geometric elements, are seen on a pot offered on Ebay, 6-6-22. That pot is dated 6-75 and was thus made two months after the pot in this collection. [A copy of the listing is on file with the records for 2017-11.]

The pot is well made and the design is coherent and precisely cut and painted, but the overall effect is repetitious and not particularly inspiring. The pot is a snapshot of this husband and wife team at the beginning of their careers and the beginning of a new tradition of carved Hopi-Tewa pottery. After 1975 Wallace would follow the lead of his brother-in-law Thomas and form thick pots that he would carve with scenes from Hopi life, often katchinas. Iris developed a plainware design of raised corn on a matte on a traditionally-fired blushed background and made versions of this form for most of her career (See 2003-08.) Interestingly, when interviewed by Gregory Schaaf in February 1998, Iris commented that “It is important to fire the pots traditionally and not use a kiln (Schaaf, 1998:107).”

It’s difficult to make a living on the reservation and Hopi and Hopi-Tewa potters have always been sensitive to the demands of the market and constantly monitor what tourists and collectors want. Pot 2017-11 is an early experiment by two talented potters inovating to find a distinctive style that would sell. Neither continued with the design techniques used on this pot; both developed distinctive styles appreciated by the market. Pot 2017-11 was an experiment, a stopping-off point.