The techniques used to make this vase are entirely Anglo; the spirit of the Katchina design entirely Hopi: A perfect summary of the life of Charles Loloma.

Vase 2011-09 was made on a potter’s wheel using commercial clay, was kiln-fired and glazed. The exterior glaze is a mottled, sandy brown. Striations in the clay on the exterior cause the glaze to be lighter in the valleys and darker on the ridges, much like the stratified variations in the sandstone at Hopi. The lip and interior are a covered with a darker, more uniform brown glaze. Parading around the exterior of the pot are nine longhaired Chakwaina katchinas engraved into the surface.

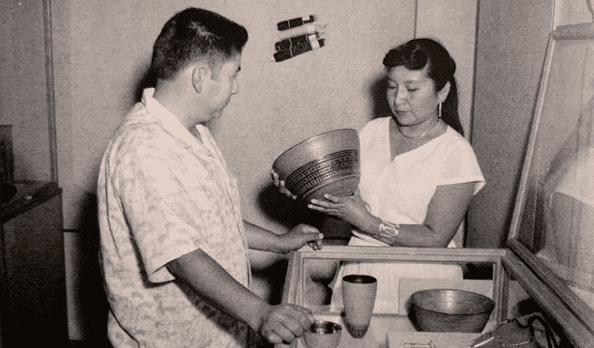

Charles and Otellie Loloma in their gallery space

at the Kiva Craft Center, ca 1956.

Source: Martha Struever, 2005:12

Loloma’s signature and the date (19)57 are scratched clearly into the base. Several paper labels are affixed to the bottom. One reads”C-3. $13.00.” The “C-3” may represent the Loloma studio inventory number. It is likely that the pot sold in 1957 for $13.00. A very similar vessel is in the collection of the Museum of Northern Arizona, though the MNA pot depicts the katchinas only from the waist up (see Streuver, 2005:42). Another very similar vessel was for sale at Shiprock Trading Company, Santa Fe, in July 2011. (Picture on file.) The Chakwaina Katchina design on 2011-09 (Colton #160) was also used in Loloma’s jewelry (Streuver, 2005:55 and 84).

Born in 1921, Loloma was about 36 when he made pot 2011-09. (Most of the biographical information about Loloma is taken from Struever, 2005.) As a child and youth Loloma was a painter. Charles married Otellie Pasivaya of Sipaulovi, Second Mesa in 1941. He was inducted into the army the following year. In 1946 Charles was discharge from the military; the next year both Charles and Otellie attended a two-year crafts program at the School for American Craftsmen at Alfred University, in Alfred, New York. They enrolled in the ceramics curriculum:

“At the outset the Lolomas did not want to appear unfamiliar with the medium of wheel-thrown pottery, so they snuck into the ceramics studio before the first class and practiced long enough to appear confident in their abilities….(Charles believed that) traditional arts should be allowed to evolve and change to reflect the realities of modern life. ‘You see,’ he said, ‘our peoples have made pottery for generations, [but it] doesn’t stand up like modern chinaware…[We] hope to give it a new life…by teaching our people about glazes….(so that) Hopis can become more self-sufficient’ (2005:9).”

The Lolomas returned to Second Mesa in 1949. For the next two years Charles received a fellowship from the Whitney Foundation for the research in ceramics on the Hopi Reservation. Although they were home, their wheel-thrown, glazed and kiln-fired pottery was not well received in the local community:

“Charles and Otellie believed their work was distinctive enough to avoid competition with traditional potters in neighboring communities; nevertheless they received considerable negative attention from their conservative neighbors. On the positive side, their pottery was beginning to sell. But they were disheartened by the criticism of their own people and reluctantly decided to leave Hopi (2005:11).”

In 1954 the Lolomas opened a pottery shop in Scottsdale, becoming the first tenants of the successful Kiva Craft Center and calling their pottery “Lolomaware.” “Charles continued to work in ceramics after moving to Scottsdale, but he also became passionately committed to jewelry (2005:12).” The Lolomas maintained a studio and shop in the Kiva Center for six years. Sometime during the Lolomas’ third year running their studio Charles made vase 2011-09. He began making jewelry in 1955. Soon after his interests became almost wholly focused on jewelry making, the craft for which most people recognize his name. He made pottery for a bit more than 10 years, about 1947 to about 1959.

The Heard Museum Guild website describes Loloma’s transition from pottery to jewelry:

“Loloma rather quickly replaced his work in clay with work in metals. For the first Heard Museum Fair & Market in 1959, a newspaper promotion declared that Loloma would demonstrate pottery-making at the Fair. The accompanying photograph actually showed him holding a carved tufa stone—a volcanic stone used for casting silver or gold. Visitors to the Fair that year purchased jewelry, and Loloma transitioned into exclusively making jewelry.”

Charles returned to Hopi in 1964 and built a home and a jewelry studio on the outskirts of Hotevilla, his home village. Otellie did not return to Hopi with him and in 1965 they were divorced. In Hotevilla he pursued and evolved his jewelry making and reentered Hopi ceremonial life, within which he had been raised. As a traditional Hopi man he planted corn and other crops and tended his garden. As an increasingly internationally recognized artist, he traveled to Europe, parked a Jaguar car outside his home, and bought a small plane (and created an air strip on the reservation). In the Anglo art world he sometimes wore a cape. Loloma stood firmly in both Native and Anglo worlds, two cultures that were often in conflict, bridging these cultures with creative genius and a strong and iconoclastic personality.

Marti Struever summarized this personality:

“Loma was a paradox. He found fame as a jeweler, potter, painter, and poet; he traveled extensively; and he seemed comfortable among affluent Euro-Americn art connoisseurs. His bold innovative designs departed dramatically from Hopi cultural beliefs, yet there was no question that he preferred to live at Hopi, one of the most conservative tribal communities in the United States,

Loloma faithfully observed the complex Hopi ceremonial and agricultural calendars. He practiced dry farming on land near his home and participated in ceremonies…In his early ceremonial roles he was an impersonator and clown, and he later became a leader in his kiva. As leader of the Badger Clan he headed Powamu –Bean Dance–…Among outsiders he kept his ceremonial life intensely private. Few who admired his jewelry knew of the enormous contrast between his deep commitment to to Hopi Tradition and his innovative artistry. (2005:2).”

By some accounts, in the mid 1950’s Loloma taught pottery making to Polingaysi Qoyawayma (Elizabeth White), another Hopi from Third Mesa who strained to live in both culture. (For a bowl by Polingaysi Qoyawayma, see 2005-08.) Twenty-five years later Polingaysi passed on these skills to her California-raised nephew, Al Qoyawayma, an aeronautical engineer who worked for NASA. (For a bowl by Al Qoyawayma see 2006-03.) Three generations of great potters rooted in Hopi culture but substantially living in the Anglo world and defined by the international art world as chic artists. Their pottery is a distinctive style in the story of Hopi pottery.