Annie Healing (Nampeyo) was probably in her late 40’s or early 50’s when she made this bowl. Signed with her name, it was clearly made to sell to tourists. However its utilitarian form, white slip and red lip reflect a Polacca polychrome tradition that was typical of Hopi pottery about the time Annie was born. In contrast, the black design is typical of the “Sikyatki Revival” style developed by Annie’s mother after 1900. The pot is full of disjunctions.

Bowl 2016-01 is in the shape of an oblong boat with its “bows” slightly higher than its sides. When the clay was still wet, one end was pinched in to form a spout. (I may well own the clearest set of Annie’s fingerprints on record.) Until the late nineteenth century such shapes were made at Hopi for home use, functioning much like the Pyrex measuring cup in your kitchen.

The pot was slipped with white kaolin clay, as was done with Polacca ware in the nineteenth century. Polacca slip is characterized by scabbing caused by the differential shrinkage of the clay body and the slip. Early in the twentieth century Annie’s mother, Nampeyo, discovered that stone polishing the slip before decoration and firing adhered the white slip and resulted in a smooth surface (Wade and Cooke, 21012:131, 140, 142). Striations caused by Annie polishing the pot with a smooth pebble are seen on jar 2016-01, most clearly on the exterior.

The decoration is a mixture of Polacca and Sikyatki Revival styles. Like the white slip, the red-painted rim on bowl 2016-01 is characteristic of Polacca ware until about 1900 but infrequently used on pots with Sikyatki Revival motifs.

As was her mother’s convention, Annie has built her black design inside thick-over-thin framing lines.

One of Nampeyo’s classic bowl designs is taken directly from a pre-historic Sikyatki model and has been given the name “bird hanging from sky band design.” (See bowl 1993-04.) Appendix B is an extensive discussion of this design and its role in refining Nampeyo’s style. One characteristic of the bird-hanging-from-sky-band design is its segmentation of the interior of the bowl. Generally one third of the painted surface was reserved for a (usually) red lunette with the rest of the surface used for an abstract avian image.

Bowl 2016-01 has a completely different design, but, following her mother’s convention, Annie has similarly divided her painted surface into two design areas, one taking exactly one third of the space.

For the design in the smaller space, Annie chose to draw two renditions of her mother’s “clown face.”

“Nampeyo whimsically tucked variations of the clown face into many designs throughout her career (Kramer, 1996:188).”

Notice that the V shape of the clown face echoes the form of the nearby spout. Above each V-shaped clown face Annie has drawn three dots.

Separating this smaller design area from the larger are three thin lines forming a two-lane “highway,” another Nampeyo convention (cf. 2014-01). A second two-lane highway runs perpendicular to the first and divides the larger design area into two separate but identical spaces.

Each segment contains a large unpainted triangular space. Intruding into the base of this unpainted triangle are two black half-domes, each sporting two vertical lines. Near the apex of each triangle is a set of three rectangular black rectangles, giving this design a bit of the look of Casper the Ghost. Although more pointed, notice how these two large white forms reflect the overall shape of the bowl. Design fits form, and both engage the eye.

If it were not signed, I would estimate that bowl 2016-01 was made in the first decade of the twentieth century and represents a mixture of Polacca and Sikyatki traditions. It does represent such an overlap of pottery traditions, but with a few exceptions (2012-25, 2015-11, 2015-14 and 2019-18), Nampeyo pots were not signed until about 1930. Barbara Kramer writes that Annie began signing her pots in the late 1920’s and that after the 1930’s suffered from arthritis which limited her pottery making (1996:162).

The Blairs note that:

“Only a few works signed ‘Annie’ have been located, and it is not known if Annie could write, so it is possible that the signature had been applied by someone other than Annie…Authentic pieces of Annie’s pottery are difficult to locate. (After her marriage about 1900 family responsibilities reduced Annie’s pottery making.) Later in life Annie was plagued by poor health and failing eyesight…. (and) was subjected increasingly to severe coughing spells as well as arthritis and required more rest than normal. Dust generated as the result of working with pottery clay did not improve the situation (1999:180. 184).”

This collection now contains five pots signed with Annie’s name, an unusually large sample.

—Priscilla Namingha, Annie’s granddaughter, once told me that Annie’s eldest daughter Rachel, middle daughter Daisy and her youngest daughter Beatrice used to sign their mother’s work for her. All three: Rachael (1994-12 and 2012-20), Daisy (2011-13 and 2019-16) and Beatrice (2002-08 and 2005-04)] sign with a lower case “e.” Two pots signed “Annie Nampeyo” in this collection (1999-13 and 2013-03) employ a lower-case “e.” Thus these two pots were likely signed by either Rachael, Daisy or Beatrice, though Beatrice died in 1942, age 30.

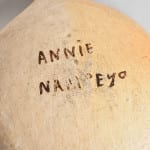

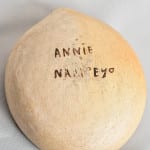

—I believe the remaining three signed Annie pots were signed by Fannie. By the age of six Fannie attended the boarding school at Keams Canyon and learned how to write when young (Blairs, 1999:69). Fannie always printed a capital “E” when signing her name or, in the case of jar 2008-01, both her name and Annie’s. Signed Annie pots (2000-06 and 2009-04) carry this capital “E” and seem to have been signed by Fannie, though the signature on the second pot seems casually applied and is shaky. Since bowl 2016-01 is also signed with a capital “E,” it is likely that Fannie also signed this pot, probably in the 1930’s. Thus three of the signed Annie pots carry a capital “E” and were likely signed by Fannie.

Given this variation in signatures and her lack of formal education, I believe that Annie was illiterate and a variety of people signed Annie’s pots for her.

Jar 2016-01 is an intriguing pot because it is tourist pottery with a utilitarian shape, its mixture of Polacca and Sikyatki Revival styles, and the rare “Annie Nampeyo” signature.