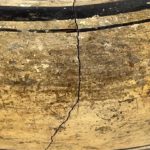

1)The design on this bowl is exfoliated and worn; the jar itself is cracked.

2) The design is evidence of the genius of its maker, Nampeyo of Hano.

Both statements are true, but the second is far more important than the first. For a collection that is trying to discover the full range of Nampeyo’s ability, bowl 2021-09 is particularly interesting. Aside from the beauty of its design, jar 2021-09 is also a test of the ability of Nampeyo to adjust design to space.

When painting, Hopi potters favor the wide interior of bowls or the wide upper surface of a jar with a flat shoulder. Both offer a broad, unobstructed canvass (Kramer, 1998:180-182). In contrast, the shape of a wide-mouth, low jar such as 2021-09 presents a narrow exterior and thus constrains the form of a design (Bunzel, 1929/1973:42). The easiest solution is to repetitively paint a single design in the narrow band around the circumference of the pot. Nampeyo sometimes adopted this strategy (2002-11) and the result is “OK,” although a bit boring. Jar 2021-09 is important because it a contrary example. Within a narrow band of surface, Nampeyo has created a design that is full of energy and interest. Thus bowl 2021-08 is a marker of Nampeyo’s extraordinary design ability.

Form:

The bottom of this jar is quite thick, evidence of having been built on a disk of clay in a puki. The walls are thinner and even but still substantial, and thus the pot seems heavy for its size. The bottom is rounded; the walls of the pot curve up smoothly 4-inches to the waist of the pot before turning inward 1.75-inches to the mouth. The mouth (4.375-inches wide) occupies two-thirds of the width of the jar, severely reducing the surface that is visible when the pot rests on a table.

The exfoliation of the exterior is an indicator that he pot once held a well-watered plant. A thin crack runs from the rim of the jar, down its exterior, to about the middle of its bottom. The crack is probably visible on the inside, but a previous owner glued a piece of cloth on the interior of the bowl over the crack, a rough effort at stabilization.

Design:

As is typical of Nampeyo, a set of thick-above-thin framing lines is drawn just below the mouth of the jar and a somewhat thinner set of framing lines, in reverse order, marks the lower boundary of design. This lower set cannot be seen when the pot is on a flat surface.

Between the two sets of framing lines is a 1.5-inch wide panel of design. The wide mouth of the jar, and its narrow upper surface, force the design to be drawn on the curve marking the waist of the jar. From below the jar is seen as a disk of blank space encircled by framing lines. From above only the upper fragment of the design panel is visible surrounding the framing lines. Only when the jar is viewed from the side is the band of design visible.

The design has two major elements and each is repeated twice on the jar. Each of the two design panels is 7.5-inches long. A curvilinear avian form accounts for 60% of this length, an ovoid element occupies 33% of the design panel. Four sets of parallel lines account for the remaining space.

Curvilinear avian form:

All of the elements that form the body of this creature are frequently used by Nampeyo. A catalog of Nampeyo bowls in this collection with these same elements of design is provided in Appendix “F.” The avian form on jar 2021-09 is much like that found on canteen 2020-17, but here is more delicately drawn. The most prominent section of this creature is a large set of tail feathers that 1) spreads to the full width of the design panel, 2) is the only red element in the design, and 3) serves as the base of the rest of the body. From the red, square comb, this element branches rearward into two red rectangular shapes that evolve into unpainted rectangles with black tips. On either side on these linear feathers, the red comb sprouts long, curved red feathers. This is a tail with a flourish, which I categorize as a tail with “red base comb, black tipped and flanked by red pointed feathers” in Appendix F.

The red comb base is caped with two parallel lines, a one-lane “highway.” In the next section, against the wall of this highway, is a black hill (“gumdrop”) that intrudes into an unpainted segment. Protruding into this space from the far wall is a clown face “(“Kilroy”) that Nampeyo frequently introduced into her designs (Kramer, 1996:188). On either side of its V-nose are small black gumdrop eyes, its head is stippled, its forehead a larger gumdrop. A thin unpainted line separates this gumdrop from the next section. In one rendition of the design, the next element is another broad black gumdrop with a parallel base; in the second rendition this gumdrop is missing. What follows is an exact duplication of the first Kilroy clown, but facing in the other direction. Thus the center of the avian figure has two Kilroy faces in sequence but facing in opposite directions. On the far wall of the second Kilroy section is another gum drop, its apex pointing toward the Kilroy across empty space. A narrow sliver of empty space (a one-lane highway) supports the gumdrop’s base.

At this point the avian form makes a radical left turn and becomes an elongated black head with a long, thin, beak. The head lacks an eye but the beak is open and reveals a thin tongue.

Broad highway:

At the upper boundary of the red comb is a set of parallel lines that I call a “highway.” Two parallel lines would form a “one lane highway,” with one lane added for each additional line. Two and three-lane highways are common on Nampeyo pots, but the highways on jar 2021-09 are the widest I have encountered, 4 lanes in one case and 6 lanes in the other. Moreover, while Nampeyo was a master of precision (look at the precise framing lines), the parallel lines on these wide highways were drawn without much attention. The lanes in the four-lane highway vary in width; the lines that define the six-lane highway also vary and one lane line collides with its neighbor.

This is not the first time I have observed this pattern. Sometimes on a finely crafted design by Nampeyo you suddenly find a casually drawn section (cf 2018-04). I surmise that when Nampeyo was painting a pot she paid great attention to the sections of design she cared about but casually drew design elements that were not her focus that day. Highways are the most common Nampeyo design element and she seems to have had little interest in their form the day she painted pot 2021-09.

Ovoid element:

On the far side of the wide highways is a ovoid form, a new design element in my collection. One rendition of this design is clear, the other the most exfoliated section of the bowl. One end of the form rests against, and is a bit truncated by, the adjoining highway. Where the framing lines intercept the highway, two thick lines emerge like struts to hold the curved form in place and keep it from rolling off the side of the pot. If seen as part of the egg shape, these thick lines are the long leg of right triangles with curved hypotenuses. As the ovoid form continue to the left, the line forming its edge narrows almost to the point of disappearing, then suddenly broadens again to a “D” shape that is the rear segment of the egg. The apex of the “D,” the rear of the egg, is multiple times thicker than any other part of the form.

On the sides of the egg where the walls are the narrowest, a two-lane highway cuts across the design. Set against its right wall are two conjoint black hills that span the width of the design. Sprouting from the valley between the hills are clustered three thin and parallel lines. On the left rear-facing side of the highway six short lines are spaced across the width of the design.

Design analysis:

While I would not have recognized the ovoid form as being “by Nampeyo,” virtually every other design element in the avian form was regularly used by her. For example, the a “tail with red base comb, black tipped and flanked by red pointed feathers,” and the “Kilroy” clown face appear on numerous Nampeyo pots in this collection, look familiar, and catch my eye. The overall form of the curvilinear serpent is a recognized Nampeyo design. (See canteen 2020-17 for this discussion.) Thus while careful analysis is needed to confirm first impressions, initially recognizing a Nampeyo pot is like instantly recognizing the face of an old friend in a crowd. It looks right; it has the right parts. It makes my collector’s eye sparkle .

However, an observant reader will notice that I have been asserting that bowl 2021-09 is by Nampeyo without offering any systematic proof. In Appendix “B” I defined six design strategies that I think characterize the painting of Nampeyo during the maturity of her career and allow us to distinguish her work from other potters. These strategies are:

1) A tension between linear and curvilinear elements, often represented as a contrast between heavy and delicate elements.

In the avian image linearity is mostly provided by the two black-tipped tails and, secondarily, by the linearity of the creature’s beak and tongue. All other elements, from the pointed red side feathers and most obviously the dramatic curve of the body are curvilinear. The egg-shaped element is, of course, curvilinear but at its center are four linear lines.

2) A deliberate asymmetry of design.

The avian figure is obviously not symmetrical, its companion ovoid element could easily be. However, the varying width of the lines that form the egg shape undermine its symmetry. The off-center positioning of asymmetric elements internal to the ovoid adds to the design’s lack of symmetry.

3) The use of color to integrate design elements.

There is only one element of color in the design, so obviously this integrative function is not fulfilled.

4) The use of empty (negative) space to frame the painted image.

Given the narrow width of the design panel, it would be difficult to surround elements of design with framing space, as is Nampeyo’s usual procedure. Instead she provides such framing space on a horizontal axis and internally to the ovoid egg.. The circumference of the bowl is about 21-inches and each design panel is about 7.5-inches long. With a bit of adjustment Nampeyo could have painted three crowded renditions of the design around the circumference of the jar. Instead she drew two renditions in the design band and left 3-inches of space between these renditions. The result is that the design does not feel crowded and is highlighted by empty space even though the avian design touches both upper and lower framing lines. The ovid shape is “self-framing,” its rear interior empty except for the four thin parallel lines. Between this interior space and the undecorated panel to its left, the egg is uncrowded in the panel of design.

5) The use of a thick above a thin framing line on the interior rim of her bowls.

Although not a bowl, this jar displays two sets of framing lines.

6) Nampeyo’s painting is confident, bold, and somewhat impulsive compared to the more-studied, plotted and careful style of her daughters, descendants and other Hopi and Hopi-Tewa potters.

As I do every time I discuss these design strategies, I need to point out that this is both the most subjective and yet the most important criteria for deciding if a pot is “by Nampeyo.”

First, the design shows confidence in ability. Fitting the avian design into a space 1.5-inches tall is not a simple task of either conceptualization or implementation. Notice how the artist has cooled off the energized curvilinear figure by placing it next to the more sedate and contained ovoid form. Notice also in the ovoid figure how the empty space to the left of the elements inside the egg is “D” shaped, as is the wide black border immediately to its left. Such subtleties of design are sophisticated acts of imagination, a consequence of confidence.

Second: Both the avian image and the design layout are bold. The feathered serpent figure is probably the most powerful image in Nampeyo’s lexicon, perhaps in the history of pottery made at Hopi. The red tail is like a rocket with side thrusters blasting off at full throttle: a powerful image. Placing all this energy between framing lines 1.5-inches apart increases the visual pressure around the image. On jar 2021-09 confidence in ability has led to boldness of both imagery and design layout.

Third: Given the constrained space, Nampeyo must have thought through her design carefully before putting brush to clay. Nevertheless, there are still a couple of impulsive aspects to the design. The better preserved of the designs has two black hills (“gumdrops”) between the two Kilroy images at the middle of the avian design. When the artist repeated the design, she left out one of these hills. One rendition of the design has a 4-lane highway between the design elements; the other has a 6-lane highway. In both cases —but especially the 6-lane version— the parallel lines are not carefully drawn and in one case the parallel lines collide. “Highway” elements between sections of design are common in Nampeyo’s work and on this jar she did not put much care into drawing them, but rather drew them impulsively.

These six design strategies are not a “rule book” that Nampeyo followed every time she made a pot, but rather tools that she could draw upon when she felt the need. I repeatedly cite them because Nampeyo used these strategies far more other than other potters and thus the overall pattern of their use can give a strong indication of whether Nampeyo was the maker of a pot or not. That the artist followed 5 of these 6 strategies on jar 2021-09 is substantial evidence that Nampeyo was the painter of this pot.

Having seen only a photograph of jar 2021-09, on 6-11-21 Ed Wade emailed me his agreement:

“You are correct it is a Nampeyo and owing to the vessels shape dates to 1905 – 1910, a Hopi House special.”

In their 2022 book titled Call of Beauty, authors Ed Wade and Allan Cooke feature Nampeyo pottery, particularly that in the Cooke Collection at The Museum of the West, Scottsdale. In the book (pages 105 to 109) Wade discusses feathered serpent images of Paluliikon and Um-tok-ina that Nampeyo used on her pottery. These serpents are closely related to the image on jar 2021-09 and another pot by Nampeyo in this collection 2020-17. Two others pots in this collection display this curvilinear avian motif: A jar by James Garcia Nampeyo (2011-08) and a large ovoid dish by Priscilla Namingha Nampeyo (2024-03).

Freshly polished bowl 2021-09 in hand, Nampeyo was faced with the problem of creating a design on this low jar. She created a design that is compelling: balance, motion, energy and engagement in a confined linear space. Both curvilinear and linear, with sufficient unpainted area, the design soars within its tight boundaries . The resulting tension intrigues the viewer’s eye. Energy contained. What was a design problem of a limited narrow design space, has been transformed into an asset that works with the design elements to create startling beauty. That’s genius.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s mural “The Last Supper,” is exfoliated. Like that fresco, the worn painting on bowl 2021-09 is still magnificent. You might think that comparing Nampeyo’s painting to that of a Renaissance master is too far a leap. If so, we disagree.