Each handle is about 0.6875″ deep.

This collection has a large number of pots by Nampeyo and these are listed both in the “Artist List” and summarized in Appendix D. Even more significantly, the collection includes a wide range of her work, from the utilitarian (2009-17) to the magnificent (2014-07) to the minor (2002-12) to the quirky (2014-17). Pot 2019-19 is an experiment that I would not recognize as by Nampeyo except for the analysis provided by Dr. Ed Wade, who gifted the vase to me.

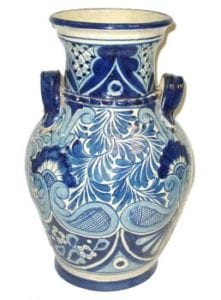

The jar has thick but even walls and is thus substantially heavier than one would expect for its size. It is lightly blushed, particularly on the lower part of the jar and may have been slipped with a cream-colored clay which is somewhat eroded, particularly on the flared neck. The shape of the jar is not at all Hopi but is European, a form transmitted to Mexico and characteristic of Mexican Talevera ware. The body flairs upwards from a substantial base, then turns inward suddenly to a narrower neck which then flairs slightly as it rises to a large, open mouth. Just below this mouth, two handles jut from the surface. Like drawer pulls, these handles have a sloped upper surface and are concave on the bottom. The jar sits with some tilt.

Talavera pottery, form

A band of design about 2.25″ wide encircles the vase below the neck. Framing bands lie just above and below this decoration, but oddly consist of three layers: a wide band bracketed by two thin bands. Nampeyo almost always placed the designs on her bowls below two-element thick-over-thin framing lines (cf. 1993-04), the order reversed on her canteens (cf 2010-11) and sometimes used framing lines on more eccentric forms (cf 2012-08). However this is the first three-line framing band I have seen. Something odd is going on here.

The design is also unusual: two creatures crouched among four plants. Each plant has four leaves attached to a long stem. The leaves are formed by two long. thin half-moons with bases facing each other but are separated by a thin, unpainted line. This same elongated half-moon element was used by Nampeyo to represent head feathers of the two birds on canteen 2019-12 in this collection. In a somewhat stouter shape, a pair of such elements was believed by Alexander Stevens to represent rain clouds (Patterson, 1994-43) and these stubbier forms are often used by Nampeyo (see 2011-16, 2012-13, 2013-03 and 2017-15, for examples). Thus it is not surprising to find this form painted by Nampeyo, but prior use has been symbolic and not as representational as is found on vase 2019-19. At the end of each stem is a black triangle formed around a red triangle with an unpainted center. I believe these represent flowers, previously an image outside of the repertoire of Nampeyo’s work that was known to me.

Animal forms were painted by Nampeyo (2012-08) and her family (2010-20) and thus the two creatures on this vase are not out-of-line with Nampeyo’s work. Ed Wade believes that the animals on 2019-19 may be badgers; another friend guessed armadillos. I don’t ever need to meet one. While certainly folky, they are carefully drawn and might well be the work of Nampeyo. [Though the version with the chip on its face is less-carefully drawn than its partner. This description is based on the better-drawn beast.]

The body is a blotchy red oval. A narrow white and stippled band begins below the head and runs under the belly, detaching itself at the rear to become a tail that arches over the back and curves down over the head. Its end displays a solid black crescent. Edging the upper back and below the tail, a thin unpainted space is outlined in black. A heartline runs from the head rearward into the body, ending with an unpainted diamond point. Somewhat similar heartlines are seen in the birds on on seedjar 2015-03 which I believe was made by Nampeyo. The beast’s head is fearsome. Entirely black, it is flat on top and then slopes to a snout. Below a gaping mouth filled with 18 teeth is a thin elongated jaw. There is no neck; the wide rear of the head emerges directly from the oval body. Small V-shaped ears sprout from the top of the head. An unpainted circle with a dot at its center provides vision. Below, two tiny feet emerge as a set at the front of the body, not a good placement to keep one’s rear off the pavement.

The more crudely-painted beast has a shorter tail than its companion and two somewhat more substantial feet placed reasonably apart under its belly. I assume its face was similar, but much detail has been lost due to an unfortunately-placed chip. On its back and below its tail the painting is casually and indistinctly drawn.. There appears to be the outline of a long black crescent on its back, but this is submerged in the red paint of its body and is difficult to discern. Above, between the body and the tail, a long red form emerges and becomes detached form the beast’s back. Otherwise the two beasties are similar.

The Allan Cooke Collection at the Museum of the West (Scottsdale) contains a curious canteen that Ed Wade identifies as by Nampeyo. Emerging from the apex of the bulbous front is the sculpted head of a bear. For our purposes, more importantly, the sides of the canteen are painted with creatures that are almost identical to the creature painted on the two sides of jar 2019-19 (Wade and Cooke, 2022:112). The bear canteen is even more eccentric than the Talavera-like jar discussed here, but its interesting that the same odd creature was painted on two eccentric pots.

Around the turn of the last century, Hopi and Hopi-Tewa bowls frequently incorporated hanging hugs into their form. These lugs would define “up” when the bowls were hung on a wall, but frequently the central axis of the interior design did not match the orientation of the lug. That same issue is seen on vase 2019-19. On a Talavera vase of this shape and design, one would expect that the animal forms would be centered between the two handles and flanked by the foliage. Such orientation is approximately true for the more crudely-formed creature, who is only a bit off-center. The more carefully-drawn beast, however, is wildly off-center. One plant emergence from the ground near the creature’s rear and this point is about centered on that side of the vase. Thus the discontinuity between form and decoration frequent at Hopi is strikingly evident on one side of this vase.

Talavera pottery, decoration

I’m not sure how to place jar 2019-19 into a history of Hopi/Tewa ceramics or the work of Nampeyo. Previous to vase 2019-19 I had not seen Nampeyo or any other Hopi potter use three framing lines in a band. The only thing essentially Hopi about the jar are the traditional spirit-breaks in these bands. However, Nampeyo did not usually indicate spirit breaks in her framing lines.

At this point I must rely on Ed Wade’s expertise and speculation. Here’s one possibility:

The pot was made during the time that Nampeyo demonstrated her craft at The Hopi House at the Grand Canyon, 1905 and 1907. There, for the first time, she was exposed to creative crafts outside of her own culture and she absorbed these images into her own fertile imagination and experimented with these new ideas. The results often seem quirky to us (cf. 2014-17), but Nampeyo was simply playing with form and paint. One result is vase 2019-19. The shape is Mexican Talevera because Nampeyo saw such a vase in Grand Canyon gift shops and wanted to try the form. The three-part banding mimics the framing lines on Talevera ware, the line breaks thrown in on a whim. (Why not?) The design layout of an animal flaked by flowers is a typical Talavera decoration; the uneven placement an indication that Nampeyo was focused on the process of creation and not concerned with the outcome.

Ed’s belief that Nampeyo saw Mexican Talavera ware at Hopi house is bolstered by a “Keystone View” stereoscopic card by Underwood and Underwood in my possession. It is titled “Inside the Hopi Indian House, Grand Canyon, Arizona” and shows shelves of basket and pottery for sale and Navajo rugs on the ground. On the reverse is a detailed discussion of both Hopi House and Hopi homes on the reservation. Hopi House, the card notes,

“is not much like the real thing. For though a Hopi family or two might might live in or near it for the entertainment of tourists, the inside is given over to curios, as the picture shows. Note a few of the objects (for sale) such as beautiful Navajo rugs…..”

The long list of curios includes “Mexican sombreros.” We know that Nampeyo and members of her family lived in Hopi House in 1905 and 1907, so this stereoscopic card is contemporaneous evidence that Hopi House sold Mexican crafts when Nampeyo was in residence. Although not mentioned specifically, the inclusion of Mexican Talavera ware is probable.

One hundred plus years later we take every Nampeyo pot as an important and serious matter. Nampeyo had no such concerns and often wanted to just play with her creative imagination, some clay, paints and a few yucca brushes. Vase 2019-19 is a result of this process.

That’s one possibility, but the actual history of this pot might be quite different. This is not the first time I wish a pot could talk.