Nampeyo (ca 1858 –1942) was illiterate and could not write, yet pots signed “Nampeyo” are known. Most, but not all, were signed by family members after Nampeyo became functionally blind. This appendix tells that story and offers some guidance on identifying who signed these pots.

Name and fame:

Nampeyo presumably began making pottery in the mid 1870s when she was a teenager and made pottery for about 70 years, until shortly before her death in 1942. Pueblo families often work together collecting clay and paint materials, forming, painting and firing pots. By 1900, Barbara Kramer writes, eldest daughter Annie was not yet 20 but she and Nampeyo:

“…worked together making pottery to sell. Typical of Hopi and Tewa custom, neither mother nor daughter sought individual recognition but set their unsigned vessels on a rug outside their home for visitors to purchase. The pottery that visitors carried away they attributed to Nampeyo (1996:76.)”

In January 1905, when she was in her mid-forties, Nampeyo opened “Hopi House” at the Grand Canyon and returned there to demonstrate her craft a second time in 1907. Both times she was accompanied by her family. By this time the Harvey Co. had made her famous and had special labels printed “Made by Nampeyo, Hopi” so they could feature her work and demand higher prices. Pots 2010-20 and 2011-16 in this collection carry this label. At times the Harvey Co., an ethnographer collecting for a museum, or a trader would order a large group of pots from Nampeyo with a single request. To meet the sudden demand, all the potters in the household would work together, as is the Tewa and Hopi tradition:

“…(W)here large groups of vessels were acquired from Nampeyo, more than one artist’s painting style is represented.,,,,(I)t is not the result of Nampeyo attempting to deceive the buyer, but reflects the traditional Hopi family approach to craft activity, in this case an effort to satisfy orders placed by traders to meet the demands of the ‘bahana’ market (Streuver, 1997:7).”

Pots in this collection that I have identified as by Nampeyo with the help of a female relative are noted in the Artist List as

“Nampeyo #2: Formed by Nampeyo and painted by a relative: Unsigned,” and

“Nampeyo #3: Formed by Nampeyo and painted by a relative: Signed.”

An early signed pot:

As noted, Nampeyo was illiterate and could not write. However, in 1906 Nampeyo made two bowls and, at the request of the buyer who printed out the name “Nampeyo” on a piece of paper, copied her name on the bowls as if copying a design. These are the earliest examples of signed Hopi/Tewa pottery and the only known example of Nampeyo’s signature written by her own hand. One of these bowls is at the Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College and the other in this collection (2015-11). It stands by itself in the collection as “Nampeyo #4: Formed by Nampeyo and signed by her own hand.”

Fading eyesight and the signing of pots “Nampeyo”:

In the 1890’s Dr. Joshua Miller had treated Nampeyo for trachoma; sometime between 1917 and 1920 Nampeyo became functionally blind from the disease (Kramer, 1996:123-124). Although too blind to paint, Nampeyo continued to form pottery for the next 20 years, until shortly before her death in 1942.

The pots that Nampeyo formed after she was too blind to paint were painted by a female relative. Sometime during the 1920’s the name “Nampeyo” began to appear on the bottoms of these jointly-made vessels. When is uncertain. Post-World-War-I prosperity brought increasing numbers of tourists to the Hopi mesas during the 1920’s, many of them wanting a Nampeyo pot. Stanislawski et al. believe that “Hopi and Hopi-Tewa potters did not commonly sign names or apply identification marks prior to the 1920’s…(1976:49).” The earliest documented example of a signed “Nampeyo” pot from this era is part of a collection of 86 pots purchased at First Mesa in 1927 by by Professor and Mrs. Carey Melville of Worcester, Massachusetts. Among these pots was a small red-slip canteen signed “Nampaya” (Walker and Wyckoff, 1983:114). The early date of this pot and its unusual spelling of its maker’s name have a significance that will be discussed below.

The stock market crash in October, 1929 and subsequent depression severely curtailed tourist travel to Hopi and there was a prolonged drought. The result was great economic suffering on the reservation (Davis,2007). Seven months later, after 50 years of marriage, Nampeyo’s husband Lesso died (Kramer, 1996:132). This must have been a very difficult time for Nampeyo, blind, alone and with a reduced demand for her pots.

Mary-Russell Colton, wife of the director of the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff was concerned about what she saw as “inferior” quality crafts being produced at Hopi during this time. In response she organized a “Hopi Craftsman”exhibit during the first week of July, 1930. Among her objectives was to encourage better workmanship by Hopi artists and create a wider market for quality Hopi crafts. (Colton, 1938 reprinted 1951:16). Cash prizes were given to encourage the makers. This exhibition continues today.

“The women (entering their pottery in the 1930 MNA exhibit) were encouraged to place their names or marks on each piece of pottery they made so that they might establish reputations for themselves, but generally speaking they did not adopt this idea (Bartlett, 1978:17).”

Thus the motivation to sign or identify the maker of a pot is entirely due to commerce with non-Natives. For a collection of late 19th and 20th century Anglo quotes praising Nampeyo’s work as “exceptional,” please see “Appendix C.” The Anglo value of promoting oneself clashed with Native values that emphasize modesty and anonymity. The promotion of Nampeyo thus caused tension:

“Preference for Nampeyo’s pieces over those of other Hopi potters, with her attendant fame, ran fundamentally counter to the values of Hopi society which de-emphasizes all forms of individual recognition; according to the famed potter’s great granddaughter, Dextra Quotskuyva, village members threw rocks at Nampeyo as she fired her pots (Streuver, 1997:7).”

Presumably these village members were Tewa, not Hopi, and were objecting to the promotion of Nampeyo as a singular artist by ethnographers, traders and the Harvey Co.

Nampeyo had a single entry in the 1930 MNA show; eldest daughter Annie entered two pieces. The family did not submit any pottery again until 1934 when

“(Three pots) made by Nampeyo and painted by Fannie were entered in 1934, 1935 and 1936.The requirement to identify the maker on each piece explains those few extant vessels bearing the name ‘Nampeyo’ printed for her by a family member (Kramer, 1996:134).”

I believe that Kramer is correct when she says that the addition of Nampeyo’s name to the bottom of pottery became more common after the MNA Craftsman Exhibit of 1930, but I remain open to the idea that the practice may have begun earlier in the 1920’s when families members wanted to capitalize on Nampeyo’s famous name, a Native substitute for the Harvey labels “Made by Nampeyo — Hopi.” Until more signed pots documented to have been made in the 1920’s are identified, however, this is just speculation on my part.

If Native values discourage recognizing individual achievement and instead encourage anonymity, why were Nampeyo family members so willing to mark pots with the signature Nampeyo? The answer might be that Nampeyo, the matriarch of Hopi pottery, was not Hopi.

Tewa or Hopi pottery?

Almost all the modern pottery we call “Hopi” is made at First Mesa, AZ, where Nampeyo lived in the village of Hano. Hano, however, is not a Hopi village but was settled by Tewa Indians from the Rio Grande Valley, 250 miles east of Hopi. On August 10, 1680 most of the pueblos in the southwest (including Hopi) revolted against the oppression of their Spanish conquerors. This “first anti-colonial revolt” succeeded in preventing Spanish return to the southwest for 12 years. After the reconquest of the northern pueblos along the Rio Grande, the Spanish forced the residents of several Southern Tewa Pueblos to settle at a new village site near the present town of Chimayo, NM. In June of 1696 both Northern and Southern Tewa revolted again and the Spanish quickly squashed the uprising. In response the entire population of the new Southern Tewa village fled to Hopi (Dozer, 1966:11).

At Hopi these Tewa refugees were given land on the eastern end of First Mesa for their homes, a village now called either “Hano” or sometimes “Tewa Village.” The top of First Mesa (600 feet above the surrounding land) is an area less than five acres large, yet it contains three villages, the other two Hopi. Walpi consists of multi-story homes and is separated by a narrow neck of land about 15 feet wide from the other two villages. Sichomovi (or “Middle Village) is contiguous with Hano and a visitor is unaware of crossing a boundary that is apparent to residents.

The Tewa at Hopi say they were invited as mercenaries to help the Hopi resist any attempts by the Spanish to reconquer lands lost in 1680. (Hopi was never reconquered.) The Hopi emphasize receiving the Tewa as an act of generosity. Today there is still tension between the Hopi and Tewa at First Mesa:

“The Tewa of Hano are staunch supporters and defenders of the cultural heritage of the original Tewa migrants…(and they) preserve their own social and cultural identify….(I)t is clear from Hano mythological traditions that the original Tewa group was not welcome in the manner it wished to be received. Subsequent unfavorable relations between the two groups have produced antagonistic attitudes and negative stereotyping on both sides (Dozer, 1966:24).”

The Hopi, of course, explain any tension very differently.

The Hopi have survived attacks by other tribes, the Spanish, Mexicans and Americans by holding fast to their culture and shielding its details from those who do not have a right to know. This conservative posture applies to pottery as well, and Ed Wade has argued that Nampeyo’s innovative career was only possible because she was not Hopi and thus not constrained by conservative Hopi standards. (Wade, 2012:12 and personal communication).

That Nampeyo’s pottery came to define modern “Hopi” pottery and some of her descendants claim exclusive right to use some of her Sikyatki Revival designs, still causes some tension with potters who are Hopi. Meanwhile many Tewa potters from Hano sign their pottery “Hopi/Tewa,” “Tewa/Hopi” or occasionally just “Tewa.”

In 1974 and 1975 Michael Stanislawski, Barbara Stanislawski and Ann Hitchcock conducted research into the use of identification mrks on Hopi and Hopi-Tewa pottery. Unfortunately their research mostly excludes discussion of the use of potters’ names on pottery. The practice of marking pottery, they found, was predominately a Hopi-Tewa characteristic: about 25% of Hopi-Tewa potters used identification marks while only 5% of Hopi potters did so. The Tewa at Hopi, they conclude, “have always been less conservative (than the Hopi)..In a sense they themselves are still foreigners to the Hopi…(1976:55).”

Thus, 1) as Tewa people feeling marginalized by the Hopi and 2) because the pottery of Nampeyo was widely publicized by and desired in the Anglo world, Nampeyo’s relatives who painted her pottery after she was blind were particularly willing to add her name to pots she formed.

Who painted Nampeyo’s pots after she was blind?

John Collins writes that:

“When (Nampeyo’s) sight became so bad that she could not paint her own designs, Lesou painted them for her until his death in 1932. Then her daughter Fannie paintd designs for her (1974:21.”

Barbara Kramer, I think effectively, disputes the story that Nampeyo’s husband Lesou ever painted for her (1996:190-191).

The Blairs report that:

“Annie was first to sign for her mother, and her printing is different than that of Fannie, who later took over the task…(E)arly cooperative works by Fannie and her mother were signed ‘Nampeyo;’ we can assume the signatures were by Fannie as her mother could not write. Later, according to Fannie, signatures on the jointly crafted pieces changed to ‘Nampeyo Fannie.’ Pottery made solely by Fannie were signed ‘Fannie Nampeyo’…(1999: 153 and 213-214).”

Note that in a different section of their book the Blairs report that “…it is not known if Annie could write” and pots that carry her signature might have been signed by someone else (1999:180). Unfortunately the Blairs do not a) specify how Annie’s “printing is different than that of Fannie,” and b) when they interviewed Fannie, they did not ask her when pots formed by Nampeyo and painted by a daughter began to be signed “Nampeyo” or when the signature began to include two names.

Similarly, published descriptions of specific pots signed “Nampeyo” assume that only Fannie helped the blind Nampeyo paint her pots. The logic behind this conclusion is:

—Eldest daughter Annie was in her mid-30’s when Nampeyo stopped painting. By then she had six children and a husband to care for and was beginning to suffer from arthritis in her hands, perhaps caused by her heavy involvement with Nampeyo’s pottery ten or more years earlier. She made little pottery in the 1920’s or after and thus probably did not paint her mother’s later pots.

—Middle daughter Nellie would have been about 24 years old when Nampeyo became functionally blind. That would be a prime age to assist her mother, but Nellie never had a great interest in producing pottery and her painting was noticeably inferior to her mother’s and of lesser quality than the painting we see on her mother’s later work.

—Youngest daughter Fannie would have been 20 when her mother went functionally blind. She was also an accomplished potter and painter and thus was most likely the painter of her mother’s later work.

This collection has signed pots by all of Nampeyo daughters and many of Nampeyo’s granddaughters. These pots provide comparative evidence that might test the assumption that only Fannie painted pots for her blind mother and signed the name “Nampeyo.” By focusing on the 5th letter in “Nampeyo it is possible to suggest who might have written the name and helped her paint her pots. The strategy is not perfect, however.

We need to determine of Nampeyo’s three daughters could write and the nature of the signatures on their signed pottery, particularly that fifth letter (“e/E”) in their last name.

Annie: Born in 1883, Annie received some schooling (Kramer, 1996:41-42), but, as reported above, in one section of their book the Blairs report that Annie could not write. .The collection has 6 pots signed with Annie’s name. Two signed Annie pots have a lower-case e in Nampeyo (1999-13 and 2013-13). Three other Annie pots have upper-case Es in Nampeyo (2000-06, 2009-04 and 2016-01). One pot is a joint product of Fannie and Annie and carries only their first names (2008-01). It is significant that the “E” in their first names is capitalized since I believe it was signed by Fannie and thus is excluded from pots possibly signed by Annie. Thus of the relevant 5 pots with Annie’s name, 3 pots (60%) have capitalized Es. In short, the form of the signatures on pots made by Annie is not consistent.

Nellie: Born in 1894, Nellie “was removed from school at an early age to assist her mother with pottery making…Although…she she seemed to lack the necessary interest (in pottery) (Blairs, 1999:203).” Jake Koopee told me that his grandmother Nellie could write. The collection has 6 pots signed by Nellie (1991-03, 1993-02, 2010-04 and 2019-08) and all use a lower-case “e” in the name Nampeyo.

Fannie: Born in 1900, Fannie attended Polacca Day School where she completed the third grade and then transferred to a dilapidated Keams Canyon Board School until she was about 10 years old (Blairs,1999:208-209). I observed Fannie writing shortly before her death. This collection includes 10 pots signed by Fannie (1981-05, 1995-12, 2001-07, 2001-07, 2009-01, 2009-14, 2012-04, 2017-12 and 2018-07) and all of them use an upper case E in the name Nampeyo. (Or in the case of 2008-01 the first names.)

Thus all of Nampeyo’s daughters had some schooling and might have learned to write their names, though we are uncertain about Annie’s ability to write. Although the sample size is small, from this pattern we can conclude that Nellie always used a lower-case “e” when signing Nampeyo and Fannie always used and upper-case “E.” It’s not clear that Annie signed her pots herself, but on her pots some have lower case “e” and some upper-case “E” in Nampeyo.

Rick Dillingham interviewed Daisy for his book Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery. Speaking of Nampeyo, Daisy said:

“Everyone painted for her — Nellie, Fannie, and my mother (Annie) helped her a lot, painted those fine lines. Rachael [Daisy’s sister] painted for her too (1994:41).”

Daisy’s comments do not specify whether these daughter and granddaughters helped Nampeyo when she was busy before she became functionally blind or only after. I suspect both. Daisy does not mention which of these painters might have signed Nampeyo’s name on her pots.

In May of 1996 I talked with Priscilla Nahmingha Nampeyo in her home in Pollaca, AZ. She was the granddaughter of Annie. I asked her who had signed Nampeyo’s name on her pottery after she was blind. She said that Annie was unable to write and that her mother Rachael and her aunts Daisy and Beatrice painted and signed for their grandmother, Nampeyo.. Priscilla did not mention either Fannie or Nellie but commented only about her own family line.

Following Priscilla’s suggestion, I looked at Annie and Nellie’s children who might have been old enough in 1930 (the date of the first Hopi Exposition) to help sign grandmother Nampeyo’s pottery. Tewa dates of birth were often not recorded, hence different sources give different estimates. None of Fannie’s children were old enough to consider. I then recorded how each of these children signed the “e” in their last name: Nampeyo. You can see each woman’s pots in the “Artist List.”

N’s grandchildren Age in 1930 Percent “e” Percent “E”

Annie, mother

Rachael 27 or 30 100% 0%

Daisy 24 or 25 71% 29%

Beatrice 18 100% 0%

Nellie, mother

Marie 16 50% 50%

Agusta 12? 100% 0%

In short, if a pot signed “Nampeyo” has a upper-case “E” in the name, it was likely signed by Fannie, though granddaughter Daisy sometimes used this form on miniature pots..

If a pot signed “Nampeyo” has a lower-case “e” in the name, it was likely signed by Nellie, Rachael, Daisy or Beatrice.

I think it probable that Annie could not write and thus did not sign pots, but if I am wrong, she used both upper and lower case “E-e” in the name Nampeyo.

I am not commenting on the results for Nellie’s children because at their young age I think it is less likely they would have had a major role in painting their grandmother’s pots. In this I am following Priscilla’s lead. Also the number of pots by these potters in this collection is very small, so the results are particularly questionable.

Guidelines applied:

This collection has 13 signed pots that were formed by Nampeyo and painted by either a daughter or granddaughter. Three are signed “Nampeyo/Nellie,” though in one case “Nellie” is represented by only the letter “N” (2003-07, 2013-12 and 2019-08). These pots display the small “e,” as expected. One is signed “Nampeyo/Fannie,” in line with our “E” expectation (2007-12). One is signed simply “Daisy Nampeyo” with a lower-case “e,”though detailed provenance says it was formed by Nampeyo (2019-16). The remaining 8 pots are signed with the single appellation “Nampeyo,” though the spelling varies and thus the 8 can be divided into two groups. The first contains 3 pots marked with a variety of inconsistent spellings of the name. The second group of 5 pots uses the usual Anglo spelling of her name: “Nampeyo,” the appellation on Harvey Co. labels.

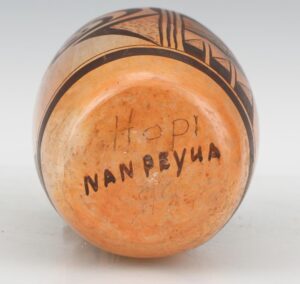

Of pots with irregular spellings of Nampeyo’s name in this collection, each uses a different spelling. Corrugated pot 2019-18 spells the name “NAMPEyuo” and based on that capital “E” I believe it may have been painted by Fannie. Round pot 2015-14 spells the name “”Nempayo” and, although the small “e” is unusually located, I believe this pot probably was painted by either daughter Nellie or granddaughters Rachael, Daisy, or Beatrice. Conical pot 2012-25 spells the potter’s name “NAMpyuo” without any “e” or “E.” Thus based on letter evidence I cannot know who painted this pot, though a story related by Ed Wade attributes this pot to Fannie ca. 1910–1915. See the pot’s catalog entry for those details. These attributions are based on thin evidence, however, and should be consider speculation. As noted above, a redware canteen collected by the Melville family in 1927 is signed “Nampaya.” An additional pot with a different exocentric spelling of Nampeyo’s name was offered by Material Culture Auctions on 4-3-23:

The capital “E” in this signature suggests that the pot was painted by Fannie.

Until the last few years, Hopi was not a written language and hence it is likely that there was no agreement within Hopi-Tewa culture about how to spell Nampeyo’s name. I suggest that pots with the idiosyncratic spellings of “Nampeyo” are attempts by her family members to translate Native pronunciations of Nampeyo’s name into the foreign language of english.

Based on this evidence, I believe that these idiosyncratic signatures predate the signatures with the spelling “Nampeyo” more commonly found of Nampeyo-formed and daughter-painted pots. I suggest that the irregular spellings were a guess about how to write Nampeyo’s name by whomever painted these pots until later Nampeyo-family painters learned the preferred Anglo spelling, then adopted that convention. The change in spelling to an Anglo form might have been prompted by the 1930 MNA Hopi show.

Of the remaining 5 pots in this collection signed “Nampeyo,” three pots are signed “Nampeyo” with a capital “E” and I believe these were painted by Fannie (2002-12, 2011-32 and 2019-18).

The two remaining pots spell Nampeyo’s name with a small “e” (1997-01 and 2010-05) and I believe that these were painted by either daughter Nellie or granddaughters Rachael, Daisy or Beatrice. The collection contains an unexpectedly large number of pots signed “Nampeyo/Nellie,” which is a surprise given that Nellie was not known as a very enthusiastic. prolific or particularly skilled artist, so numbers alone would suggest Nellie as the maker.

Of the three granddaughters, I suggest that Daisy was a particularly gifted painter and helped her grandmother more than is generally recognized. Sometimes Daisy signed her name with only her first name or an identification mark (2000-10, 2007-07 and 2007-08). Of her signed work including the name “Nampeyo” in this collection, two free-standing pots pots use the capital “E,” but note that these are both miniatures (2007-02 and 2015-07). One miniature pot use a lower case “e” (2022-01). Necklace 2022-12 contains 11 additional miniature pots by Daisy. Four are either not signed or are signed with initials. Of the remaining necklace pots, five use a small “e” in “Nampeyo” and two likely display a capital “E,” but these signatures are not clear. Four full–sized pots by Daisy in this collection are signed with the lower case “e” (1994-08, 2011-13, 2019-16 and 2020-05). I have reviewed a number of other full-sized pots signed by Daisy that are available online and all were signed with the lower-case “e.” Based on this additional data, I believe Daisy generally used the lower case “e” when signing pots, reserving the upper case “E” for a few miniatures, where the larger letter may be more readable than the smaller letters.

Of course the three lower-case “e” pots signed “Nampeyo” in this collection may have been painted by different daughters or granddaughters. Thus the origin of pots with a small “e” is less certain than pots that carry Nampeyo’s name using a capital “E.”

The above strategy yields results that are unstable for many cells due to the small number of pots in any category. It would be a relatively easy task for a museums or other collectors to plug their data into this format and determine how the pattern of results change.

I look forward to the discussion.